The History of Citrus Heights

Early History and Native American Presence

Photo source: “The Savages Were in the Way”: California’s History of Genocide, Truthout (Nov 9 2017)

The Citrus Heights area sits within the broader homeland of the Maidu—often called the Nisenan in the lower Sierra foothills and valley. Villages clustered near dependable water and oak groves, with seasonal rounds to salmon runs, seed meadows, and upland hunting grounds. Houses could be semi‑subterranean in winter villages, complemented by granaries for acorns and seeds.

Acorns from valley oaks were a dietary cornerstone. Families leached tannins with water, then ground the meal for porridges and breads. Basketry—renowned for its craftsmanship—supported food processing, storage, and gathering. Controlled burning maintained open woodlands, stimulated seed plants, reduced pests, and refreshed browse for game, reflecting sophisticated ecological stewardship.

Trade routes connected communities across the valley and foothills. Items such as shell beads, obsidian, pigments, and finished baskets moved across cultural networks, while oral histories and place‑based knowledge encoded navigation, resource timing, and ceremony. The arrival of colonists brought epidemics and displacement, yet Maidu descendants remain in the region and continue cultural revitalization today.

Spanish and Mexican Periods

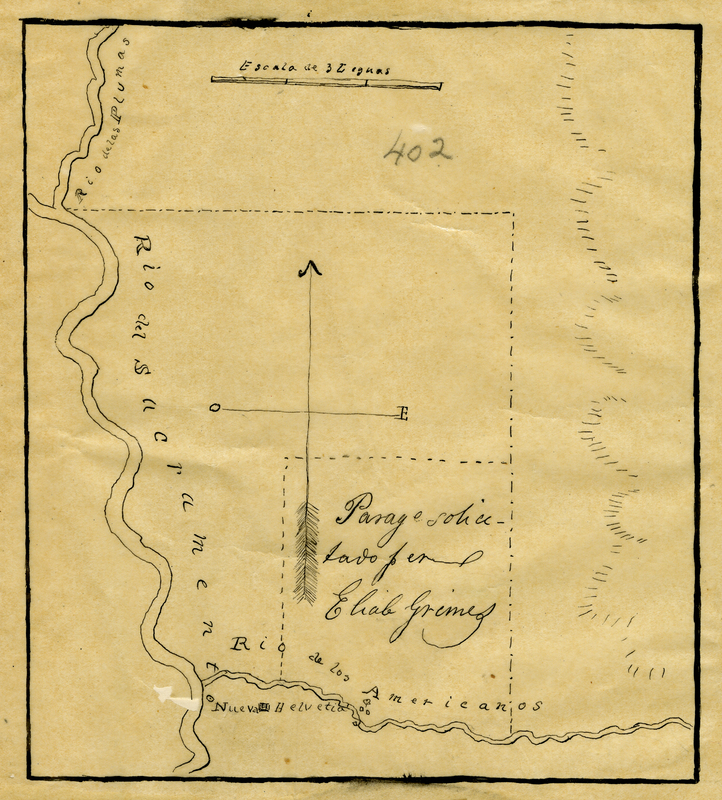

© California State Library

In the late 1700s the region that would become Citrus Heights lay beyond the established Spanish-mission frontier, but it was far from untouched. Spanish expeditions passed through the Sacramento Valley, and the area’s oak savannas, streams, and indigenous trade networks were well known. Although missions were concentrated nearer the coast, Spanish rule asserted legal and territorial frameworks that would have lasting impact.

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, California’s administration introduced the secularization of mission lands and shifted toward a new ranch-based economy. Under Mexican governance, vast land grants were issued across California. One of these, in 1844, was the massive Rancho del Paso—approximately 44,371 acres—granted to Eliab Grimes, and one of his associates. The grant covered land that now includes parts of north-Sacramento County and the future city of Citrus Heights.

The name Rancho del Paso—Spanish for “the passage”—captured the geography and purpose of this land: a gentle crossing between the Sacramento Valley and the foothill trails leading toward the Sierra Nevada. Through this corridor, herds and wagons moved seasonally, linking early ranchlands to the trading routes and river landings that sustained interior California.

Granted in 1844 under Mexican rule, Rancho del Paso encompassed more than 44,000 acres that included today’s Citrus Heights. Its open range and riparian woodlands supported a vibrant ranching economy built on cattle, wheat, and hides. Life here reflected a fusion of Spanish, Mexican, and Indigenous traditions—horsemanship, craftsmanship, communal labor, and hospitality—creating one of the earliest multicultural landscapes in the Sacramento region.

Latino Californios, vaqueros, and artisans brought generations of skill to the rancho system, introducing methods of irrigation, animal husbandry, and field management suited to California’s Mediterranean climate. Their artistry and stewardship shaped the region’s working rhythm and left enduring marks in the state’s language, place names, and sense of community.

Across this countryside stood adobes, wood-frame dwellings, corrals, and watering places. Indigenous Maidu and Nisenan peoples—whose ancestors had long tended these valleys—interacted with the ranches through trade, labor, and seasonal work, even as land tenure and cultural balance shifted under the pressures of colonization.

The close of the U.S.–Mexico War (1846–1848) and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo placed California under U.S. sovereignty. The Land Act of 1851 required Mexican land grants to be proven in court; Rancho del Paso’s claim was filed in 1852 and patented in 1858. These legal transitions redefined ownership, opened the door to subdivision, and set the stage for the agricultural communities that would eventually form Citrus Heights.

The legacy of this era endures—in the stories of Latino ranch families, in the layered cultural landscape, and in a shared regional identity that continues to honor both its Hispanic and Indigenous roots.

The Gold Rush and Settlement

When gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma in 1848, just northeast of today’s Citrus Heights, California and the Sacramento Valley changed overnight. Within months, fortune-seekers from across the world poured into the region, transforming a quiet ranching outpost into one of the most dynamic frontiers on the continent. The influx of miners, merchants, and settlers triggered the creation of supply routes, ferry crossings, and trail systems that stitched together what would later become the suburban heart of Sacramento County.

Yet the Gold Rush’s prosperity came with deep human and environmental costs. The Maidu and other Native peoples—who had lived sustainably along the creeks and oak savannas for thousands of years—were forced from ancestral lands by disease, violence, and resource exploitation. Contemporary scholarship and tribal oral histories characterize this era as a critical juncture of cultural loss and displacement for Native communities across Northern California. [Truthout, 2017]

Meanwhile, Sutter’s own fortunes declined as squatters and speculators claimed parcels of his once-vast holdings. Following California’s admission to the Union in 1850, the Rancho del Paso lands were gradually subdivided and sold. The fertile loam soils, reliable groundwater, and mild Mediterranean climate proved ideal for orchards and row crops. German, Swiss, and Midwestern families purchased small tracts to grow fruit, nuts, and grains, establishing the patchwork of farms and lanes that would define the area for the next century.

As the century progressed, small agricultural communities formed around wagon routes and stage stops connecting the foothills to Sacramento. These corridors—later paralleled by Auburn Boulevard and Greenback Lane—became arteries of commerce and migration. Although the Gold Rush had faded by the 1860s, its infrastructure legacy endured: roads, irrigation ditches, and informal trade networks laid the groundwork for the communities that would eventually coalesce into Citrus Heights.

The Gold Rush thus represents both the catalyst for settlement and the beginning of a transformation from Native homeland to agricultural frontier. Its complex legacy is visible today in place names, preserved artifacts, and the enduring spirit that continues to characterize the region.

Birth of Citrus Heights (Early 20th Century)

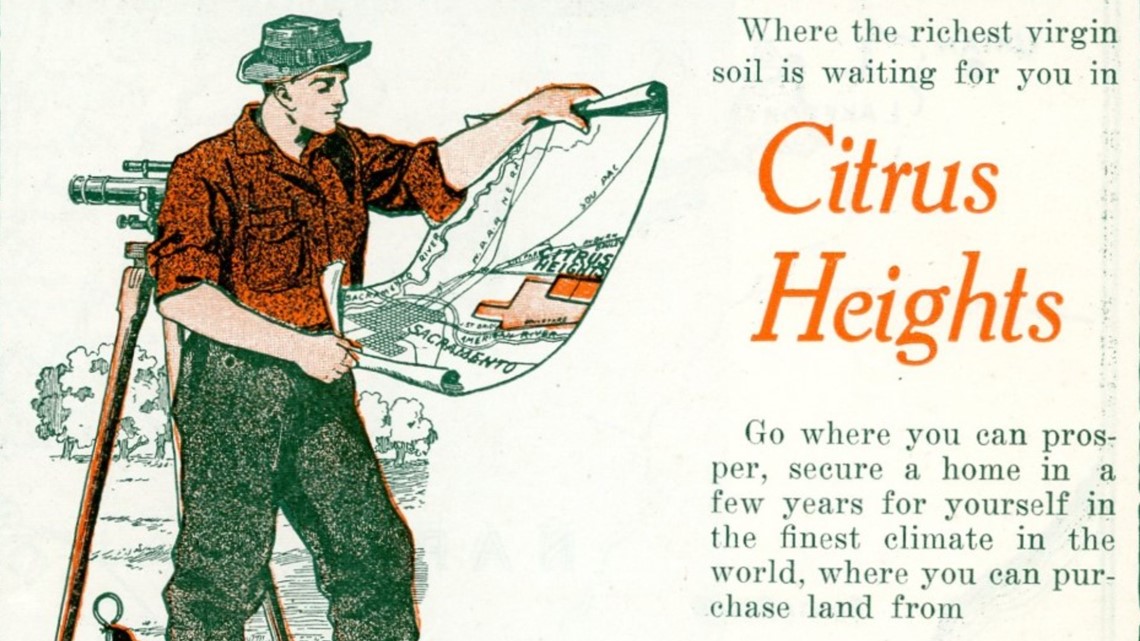

By the early 1900s, large ranch holdings were increasingly subdivided. Reliable water from local companies and small ditches supported orchard irrigation, and citrus—especially oranges and lemons—joined walnuts, almonds, and stone fruits as signature crops. Nurseries and packing sheds appeared along key crossroads, reflecting the area’s growing agricultural identity.

Improved county roads and regional rail connections opened markets in Sacramento and beyond. Freight movements became more predictable, and residents could more easily access services and supplies. Small stores, blacksmiths, and farm‑supply outlets clustered near intersections, giving the area a distinct rural‑town character.

In 1910, business leaders organized the Citrus Heights Chamber of Commerce to promote local commerce, host community events, and advocate for investment in roads, lighting, and water infrastructure. As the population grew, neighborhoods rallied around their schools and social clubs, and the name “Citrus Heights” reflected the orchards that defined the upland landscape.

Development & Suburbanization (Mid-20th Century)

In the decades following World War II, the Citrus Heights area entered a period of rapid transformation that would redefine its landscape, economy, and community life. Returning veterans, buoyed by the G.I. Bill and the postwar construction boom, sought affordable homes outside of Sacramento’s increasingly crowded core. Developers quickly recognized the opportunity presented by the area’s rolling terrain, proximity to employment centers, and access to newly expanded highways such as U.S. Route 40 (later Interstate 80).

By the mid-1950s, former orchards and small ranch parcels were being subdivided into modest residential tracts featuring single-story ranch-style homes, curving cul-de-sacs, and community parks. Street names such as Sunrise, Oak, and Mariposa echoed the agricultural and natural heritage of the region even as it urbanized. New schools—like San Juan High School and Arlington Heights Elementary—sprang up to serve the influx of young families, anchoring the area’s first generation of suburban residents.

Shopping centers and small commercial corridors soon followed, creating a self-contained suburban economy that allowed residents to live, work, and shop locally. Among the most significant developments was the construction of Sunrise Mall, which opened in 1972 as one of Northern California’s premier regional retail destinations. Its climate-controlled interior and ample parking reflected the suburban design ideals of the era—automobile accessibility, convenience, and modern comfort.

Transportation improvements were central to this suburban expansion. The conversion of Auburn Boulevard from a rural highway to a major arterial, and the eventual completion of Interstate 80, linked Citrus Heights more directly with downtown Sacramento and the burgeoning suburbs of Placer County. Bus routes and park-and-ride facilities extended regional commuting options, solidifying the area’s role as a vital residential hub in the greater metropolitan network.

During the 1960s and 1970s, civic groups, PTAs, and volunteer fire associations became the social glue of the growing community. Organizations such as the Sunrise Recreation and Park District and local service clubs invested in neighborhood amenities—ball fields, playgrounds, and swimming pools—that embodied the optimism of mid-century suburban life. Churches and small business centers reinforced a sense of belonging among residents who were still technically part of unincorporated Sacramento County.

Architecturally and culturally, Citrus Heights mirrored the American suburban ideal of the era—tree-lined streets, affordable tract homes, and close-knit neighborhoods—but with a distinctly Californian flair. The local economy shifted from agriculture to service and retail, with many residents employed in nearby defense, aerospace, and state government sectors. While the area lacked a formal city government, its residents developed a strong sense of civic identity that would later drive the successful incorporation movement of the 1990s.

By the end of the 1970s, the transformation was unmistakable: the once-rural community of orchards and open range had evolved into a thriving suburban landscape. Yet the enduring community networks and family-oriented character that emerged during this period still define Citrus Heights today—an enduring testament to its postwar growth and grassroots spirit.

Incorporation as a City (1997)

After decades of transformation from a rural farming area into a mature suburb, the residents of Citrus Heights reached a pivotal milestone on January 1, 1997 when the community officially incorporated as the City of Citrus Heights. This achievement marked the culmination of nearly two decades of debate and activism for local control.

The incorporation vote was held on November 5, 1996, passing with about 62.5 percent of voters in favor of cityhood. With this decision, Citrus Heights gained the authority to manage land use, roads, policing, and budgeting — responsibilities that had previously been handled by Sacramento County. For many residents, this was not just a bureaucratic change, but a statement of self-determination and civic pride.

The path to cityhood was anything but easy. Incorporation advocates — most prominently the Citrus Heights Incorporation Project — had spent years organizing, gathering signatures, and countering resistance from Sacramento County officials who feared the fiscal impacts of losing one of their largest unincorporated areas. The process involved multiple legal challenges, including disputes before the Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO), which governs city boundary changes in California.

Among the key motivations for incorporation were:

- Local Control: Residents wanted decision-making authority over zoning, roads, and parks, rather than deferring to a distant county government.

- Efficient Services: Many believed a local city council could deliver faster, more accountable services — from code enforcement to recreation programs.

- Fiscal Transparency: Supporters argued that locally managed tax revenues would better reflect neighborhood priorities.

- Community Identity: Civic leaders emphasized that incorporation would affirm Citrus Heights’ distinct identity within the Sacramento metropolitan area.

After the successful vote, five inaugural City Council members were sworn in on January 1, 1997, and the city immediately began operating under a contract city model — contracting with Sacramento County and private entities to deliver essential services while developing its own administrative departments. This efficient model helped stabilize finances during the early years of independence.

The city’s first tasks were ambitious: drafting a General Plan, securing a temporary city hall, negotiating service agreements, and establishing a local police presence. By 2006, Citrus Heights had launched its own Police Department, symbolizing a new level of autonomy and community trust.

Incorporation also opened the door for long-term economic planning and infrastructure development. With zoning power and redevelopment tools, the city was able to guide commercial investment along the Sunrise Boulevard corridor and begin strategic planning for the eventual revitalization of the Sunrise Mall — later reimagined under the “Sunrise Tomorrow” framework.

Cityhood gave residents a tangible sense of ownership. Civic programs like the Citrus Heights Neighborhood Associations (CHNA) and volunteer-driven REACH network emerged, creating new channels for public participation. The annual State of the City address became a forum for celebrating local achievements and reaffirming transparency in governance.

As of today, Citrus Heights remains one of the more recent incorporations among California cities. Its success as a financially stable, self-governing community — without imposing local utility taxes — is often cited as a model of prudent city formation. The effort demonstrated that grassroots civic organization could overcome bureaucracy, laying the groundwork for a responsive local government still evolving nearly three decades later.

Modern Citrus Heights

Today Citrus Heights is home to more than 87,000 residents and reflects a diverse mix of suburban neighborhoods, parks, and retail hubs. The city’s design blends mid‑century subdivisions, mature tree canopies, and newer infill housing that collectively sustain a comfortable, human‑scaled environment within the larger Sacramento metropolitan area.

City planners and civic groups have worked to maintain the balance between established character and modernization. Streetscape enhancements, storm‑drain upgrades, and expanded pedestrian and bicycle connections aim to link neighborhoods while easing car dependence. Public art and pocket parks continue to emerge through cooperative city‑community partnerships.

The Sunrise Tomorrow redevelopment project—centered on the aging Sunrise Mall property—embodies the city’s next chapter. Envisioned as a mixed‑use district with housing, entertainment, and green space, it seeks to transform the once‑regional retail hub into a walkable, live‑work‑shop core. Civic engagement remains integral, as residents help shape land‑use plans, sustainability goals, and aesthetic guidelines.

Local identity is also reinforced through community events, small‑business programs, and historic preservation. Longtime landmarks such as Rusch Park and the Sylvan Library have been revitalized alongside new civic spaces. Through these combined efforts, Citrus Heights continues to evolve as a connected, forward‑looking city that honors its agricultural and suburban roots while investing in a resilient, inclusive future.

How Citrus Heights Got Its Name (ABC10)

How Citrus Heights Got Its Name (ABC10)